The complexities of addiction have stumped scientists for decades. Today, with 48 million Americans suffering from a substance use disorder, and alcohol and drugs combined resulting in over a quarter of a million deaths annually, the urgency to find answers has only risen.

At the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, researchers are looking for genetic links, studying personality traits and seeking new therapies for addiction. Their hope is to someday not only ease the heavy cost addiction places on individuals, families and communities, but to possibly prevent it.

“Drugs of abuse tap into normal brain functioning, sabotaging normal brain circuits that are critical for adapting our behavior to our environment,” said Susan Ingram, PhD, professor, vice chair of research and the Richard Traystman Endowed Chair in the Department of Anesthesiology. “Understanding how drugs change these circuits help us to find cures and strategies to alleviate pain and drug addiction.”

What role does nature play in addiction?

When someone who is prone to addiction – for reasons scientists are still working to understand – experiences an addictive substance, it triggers a cascade of chemicals in the brain. Eventually, they crave the “substance,” whether it’s alcohol, opioids or the winning pot in a gambling game. The urge for more begins to override everything – obligations, relationships, social activities – despite the destruction it brings to their lives.

There is a physiological basis behind the urge. Ultimately, substances prone to abuse impact the brain’s reward center, an essential system for learning meant to encourage survival tactics – such as seeking and consuming water, salt and sugar. Certain substances and drugs can trigger compulsive behaviors and ultimately a substance use disorder, when interacting with the same reward pathways in the brain.

Through her work Ingram hopes to help pinpoint further the biological differences within a brain interacting with pain and chronic drug use. Some of her recent research involves methamphetamine and a specific brain receptor that appears to show the natural aversion some might have to methamphetamine use.

Methamphetamine is a powerful stimulant for the central nervous system that causes feelings of euphoria and increased energy. However, it has significant potential for addiction and serious negative health effects. While it is sometimes prescribed for attention deficit disorder, its primary use is as a recreational drug – 2.5 million Americans currently have a substance use disorder involving methamphetamine. The drug’s use has been on the rise and has resulted in an increasing number of psychiatric hospitalizations.

Ingram said methamphetamine is so potent because it quickly crosses the blood-brain barrier. The drug interacts with the reward system and entire body due to its access to the monoamine systems, which govern reward, arousal, emotion and some memory function.

Ingram is studying the trace amine-associated receptor 1, or TAAR1, which is a target for methamphetamine in the monoamine system. In animal models, her team has identified that mutations in this receptor are inheritable and play a large role in aversion (or distaste) to methamphetamine.

In lab results, her findings suggest heritability plays a large role in methamphetamine addiction.

“The impact is huge,” she said. “It’s 60% of the heritability, which is one of the most impressive single-gene effects in drug addiction that has ever been described. TAAR1 function is associated with aversion to methamphetamine. A single-point mutation in the receptor can be the difference between aversion, or strong rewarding effects and addiction, to a drug like meth.”

There is still much to learn, including more about TAAR1 gene mutations in humans and how they affect human behaviors, Ingram said. “We’re just tapping the surface of how these TAAR1 receptors work for drug addiction,” she said. “We’re really trying to understand these receptors and are hoping to look next in specific brain areas that are involved in aversion circuits – like the lateral habenula (a pea-sized part of the brain described as an ‘anti-reward center’ that scientists have found can play a role in stress responses and decision making).”

Ingram’s work comes at a crucial time, given the potency methamphetamine possesses, the health impacts it can cause and that it ranks second – behind synthetic opioids such as fentanyl – in drug deaths in the country.

One insidious aspect of AUD: heritability

In his lab across campus, Joshua Gowin, PhD, an assistant professor in the department of radiology, is doing similar work, but exploring a different substance taking an increased toll on the country lately: alcohol. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention noted a 29% increase in alcohol-related deaths over a four-year stretch – totaling 178,307 in 2020-2021, and alcohol use has become a leading cause of liver transplant in the U.S.

Similar to methamphetamine, alcohol and alcohol use disorder (AUD) creates challenges for patients, providers and researchers, given its chemical structure. It starts with its molecular nature, Gowin said.

“It’s this tiny molecule, compared to caffeine or THC (the psychoactive portion found in cannabis), which are much larger molecules,” he said. “Because of this, alcohol gets in your bloodstream and then gets distributed all around your body – there’s no part that is immune from being affected.”

That extends – in part – to one of the more insidious aspects of AUD and other substance use disorders – heritability. The heritability for AUD is around 50%, which Gowin notes comes from years of studies involving twins.

“The genes that affect metabolism are the most important genes for determining someone's risk for alcohol use problems,” he said. “We’ve determined this because the metabolic pathway is so well characterized, specific to the liver and the time course of the metabolism.”

Gowin said a genetic predisposition can be seen in certain populations. The gene is more common in people of East Asian ancestry, for example, who experience a flushing of the skin when they drink due to the rate of alcohol processing by enzymes in the liver. It’s unpleasant, and as a result, people with this genetic variant tend to be at lower risk for developing AUD.

While metabolism and heritability aspects have become better understood, Gowin has also seen the conversation change around alcohol and health.

“We’ve seen an improved understanding of alcohol’s role in promoting cancerous tissues and other health impacts,” he said. “Specifically, alcohol has both acute and chronic effects on the brain. From short-term memory impacts to longer-term consequences of a reduction in gray matter – a tissue in your brain and spinal cord that helps govern things such as emotions, movement and memory. Everything else being equal, the more someone drinks, the less gray matter they will have.”

Discoveries such as these have led to a growing conversation among healthcare providers – who have also connected alcohol to risks for diabetes and cancers, in addition to being in a vehicular accident – about the need to move away from recommending any alcohol consumption to patients.

How does environment enter the picture?

While biology is critical to understanding addiction – with genetics accounting for roughly 50% of the risk for developing a substance use disorder – that still leaves a pressing question: What about the other half?

At CU Anschutz, researchers like Drew E. Winters, PhD, are exploring the impact of environmental factors. A research faculty member in the Department of Psychiatry, Winters focuses on the intersection of cognitive control, social cognition and neuroscience, asking how our relationships – and our ability to understand and navigate those relationships – can shape the trajectory of substance use.

Changing attitudes

During his career, Joseph Sakai, MD, associate professor and addiction psychiatrist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, has seen a seismic shift in substance use research and care.

“When I started, there was less interest in the medical community around substance use disorder work,” said Sakai. “I remember one of my first patients came in with pancreatitis and also had severe alcohol use disorder. We treated his pancreatitis and sent him on his way. I was confused as a trainee about why we didn’t treat his alcohol use disorder.”

What led to things changing? A new generation of researchers and providers going through the two waves of the opioid crisis – in the 1990s and 2010s.

“My lectures used to include a justification on why discussions on substance use was important,” said Sakai. “Today, students come in, and they're immediately on board. It’s a refreshing change to see this get better.”

“We often treat social context as background noise,” Winters said. “But in reality, it’s a critical component shaping behavior. The people we’re connected to, how we read their emotions, how we respond to their feedback – that’s all data the brain uses to make decisions.”

Winters’ work takes a nuanced closer look at empathy – not as a buzzword, but as a measurable, trainable psychological skill with neural underpinnings and behavioral consequences. He distinguishes between cognitive empathy (understanding another’s perspective) and affective empathy (feeling concern for others). It’s an expansive view of the field that complements what researchers know about genetics and neuroscience with something also vital – the role of human connection. His recent research shows that adolescents with greater capacity for empathy, particularly cognitive empathy, are more likely to recognize how their substance use impacts others and become more motivated to change.

“Empathy gives us access to social information,” he explains. “It allows us to understand how our actions affect others and helps us identify whose perspectives to consider more seriously when deciding how to act.”

In a longitudinal study of over 3,300 adolescents in treatment, Winters and colleagues found that increases in cognitive empathy predicted greater responsiveness to social consequences – things like losing trust, damaging relationships and realizing one’s behavior is causing harm. That responsiveness, in turn, predicted a steeper decline in substance use over time.

From an ‘empathy deficit’ to possibility

This is where the narrative shifts – from one focused on empathy deficits to one centered on empathic potential. Winters emphasized that empathy is not a fixed trait, but a strategic tool. It can be cultivated, modeled and strengthened through experience, relationships and structured support.

That possibility is especially important in treatment settings. Many individuals entering substance use treatment have experienced rejection or exclusion – from family, school or peer groups. In that void, they may find belonging in tight-knit, substance-using groups, where drug use becomes not just a behavior but a form of connection. Over time, these dynamics can feel more stable and familiar than relationships outside that circle.

“Substance use can be conflated with social closeness,” Winters said. “People aren’t just using substances to escape. Sometimes, they’re using substances to belong.”

This insight drives Winters’ advocacy for empathy-based prevention and recovery strategies. “By helping people understand how their behavior affects others – and making clear that others genuinely care – we can reshape how they relate to the world, and to themselves,” he said.

Family patterns, cultural norms

For Joseph Sakai, MD, associate professor and addiction psychiatrist at the CU School of Medicine, the environmental effects play a clear role alongside genetics.

“Say you grow up in a household where you experience trauma, or a family member grows cannabis in the basement, or where family members model regular substance use as normative,” Sakai said. “Within each family, children learn and develop a sense of what’s normal from their environment – and these shape a sense of acceptability.” Availability of substances matters, too, and can vary within families. “We’ve seen that the perceived risk of using substances and the availability of substances generally track with adolescent use patterns.”

Focusing on the person

A cultural change around discussing substance use has also included a shift in terminology and a heightened medical focus, said Joshua Gowin, PhD, an assistant professor in the Department of Radiology.

“With alcohol specifically, there was a time where even in professional settings we would call someone an alcoholic, alcohol dependent or an alcohol abuser,” Gowin said. “The current shift is to respect their personhood with respect to alcohol use disorder and treat substance use disorder as a medical condition.”

Sakai said the model applies to a broader scale within a community – or even country – a point Gowin echoes.

“Cultures vary so much in the role that alcohol plays in society, not only how much you drink, but the way that you drink,” Gowin said. “One study compared drinking cultures in France versus in Ireland. The amounts of alcohol consumed in Ireland and France were similar, but French drinkers had a tendency toward consistent wine with dinner. While in Ireland it was a tendency to binge-drink, and that led to higher rates of heart attacks.”

Further compounding matters, Sakai said there are even gene-environment correlations.

“If someone comes from a family that has a higher genetic loading for substance use disorder, they can grow up in an environment where they are exposed to substance use disorder earlier,” Sakai said. “This can cause a sort of double whammy for some kids."

Putting people first

With such a complicated mix of factors – environmental and genetic – that are both generating further understanding, where do providers and researchers need to look first?

For Winters, any conversation around the field of substance use should start with the human connection.

“Addiction is not as easy as just stopping,” he said. “I know that’s not particularly novel but think of anything that you might struggle with – such as checking social media. That can happen with addiction as well, right? ‘Just quit’ can be an easy refrain, but I think bringing compassion to those – no matter how similar or different they are from you and decisions they’ve made and where they're at in life – is vital. I think broadly in society, it is critical that we strive to have more empathy for one another.”

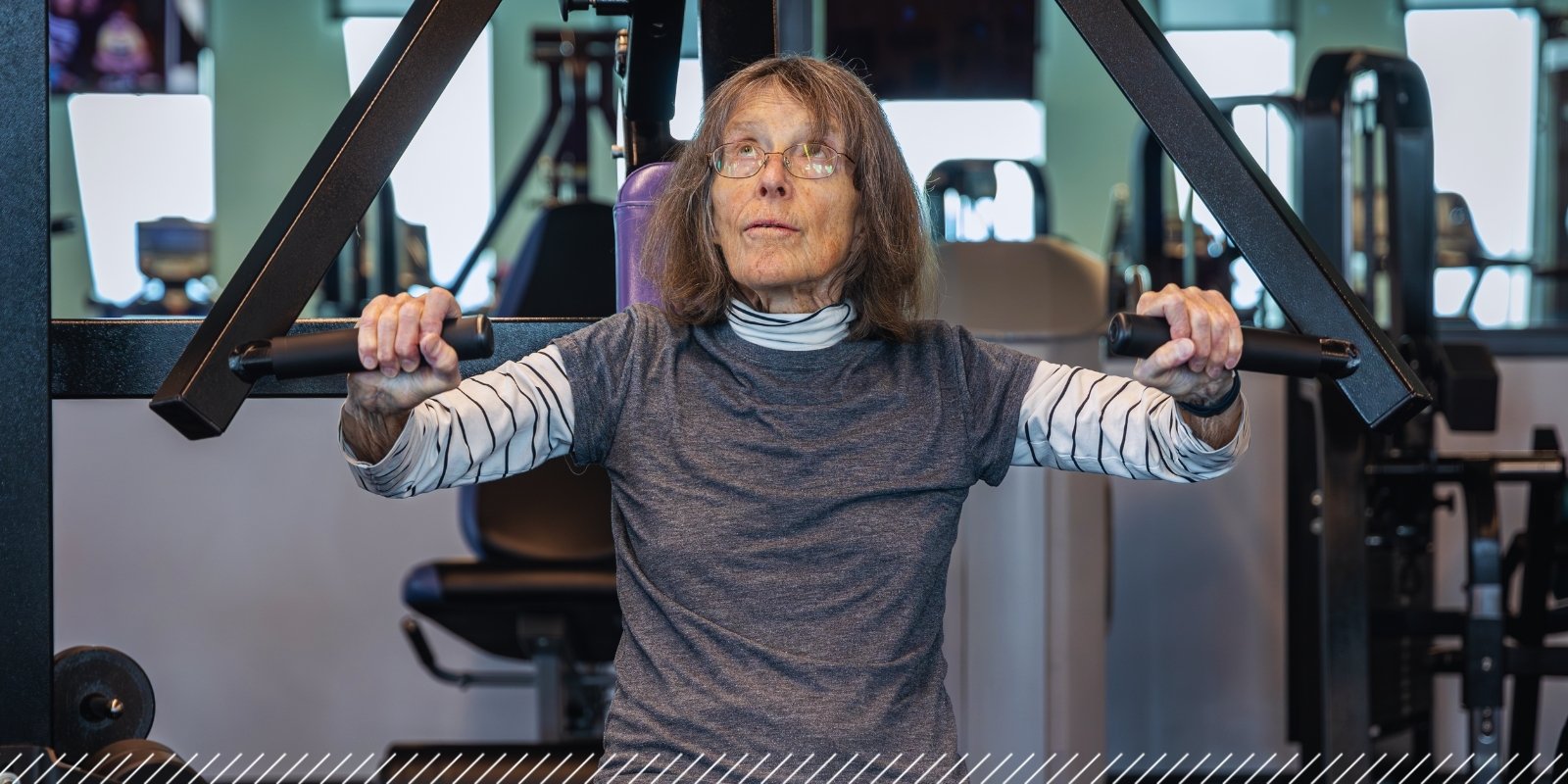

In the next installment of our series, we hear from a patient in recovery and how her recovery journey is both universal and individual.

An excerpt: A little over a year ago, Racquel Garcia’s dad died. After 15 years of not having a drink, the feelings came on hard. It was 60 days after he passed, and on a Tuesday at nine in the morning, Garcia wanted a margarita. “When those feelings came up, I knew I had to go back to my recovery community. I had to go back to therapy. Recovery is a never-ending story.”